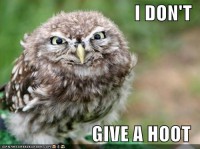

Recently, I have been wanting a particular thing to happen in my life. And I mean REALLY wanting it. My mindfulness practice continuously teaches me that grasping after desires creates suffering, whereas trusting events to unfold in their own way, at their own pace, generates ease. When we can relax into our life, as it is, we feel more peace and contentment. But this practice of letting go of hoped-for results is no easy task, particularly in the outcomes-obsessed present-day United States. I therefore am consistently on the lookout for tips about approaching life with open palms (i.e. not trying to control everything!). Happily, an acupuncturist just introduced me to a new concept: becoming hootless.

Hale Dwoskin describes hootlessness as follows:

Hootlessness is when you do not give a hoot whether you achieve a particular goal or not. Contrary to popular belief, you do not attain your goals when you desire them strongly enough. In fact, if you honestly examine your past experiences, you'll discover that most of the goals you've achieved are the ones that you let go of wanting--even if not by choice...When you allow yourself to release to the point where you are hootless about getting your goal, two things may happen. Either you'll find that you abandon the goal altogether and feel lighter because of it, or you'll be much more likely to achieve the goal than you were when you wanted it...The more hootless you feel, the freer you are to enjoy whatever you have in this moment without the usual fear of loss or disappointment.

What hootlessness amounts to in my book is a deep trust in our ability to handle whatever arises in our lives. In short, fear does not run the show, wholeheartedness does. This does not mean NOT having goals. It means relating to our goals in ways that allow us to be present to our lives, the people in it, and our environment. Hootlessness also allows us to approach life more flexibly instead of with a ton of rigid expectations, rules, and regulations. As Dwoskin points out, our wanting mind is often seeking approval, control, security, or separation. When we are able to name what we want and release our hopes and fears about how we are going to get there, space appears and we experience more freedom.

I appreciate Dwoskin's attention to language when we set goals. In his words,

'I allow myself to...,' 'I can...,' or, 'I open myself to...' are good ways to begin a goal in courageousness. 'I have...' is a good way to begin a goal in acceptance. 'I am...' is a good way to begin a goal in peace. These ways of starting a goal statement enable the mind to use its creativity to generate possibilities of how the goal can happen.

Here are a few of his courage-based goal statements that I find particularly useful for clients and myself:

- * I allow myself to feel like I have all the time in the world. (This one challenges the scarcity model dominating U.S. culture.)

- * I allow myself to have a loving relationship that supports me in my freedom and aliveness. (This one frames the setting of boundaries with others as an act of self-care.)

- * I allow myself to love and accept (or forgive myself), no matter what. (Hooray for self-compassion!)

- * I allow myself to be at peace, relaxed in the knowing that all is well and everything is unfolding as it's supposed to be. (Enough said.)

When I follow Dwoskin's advice by being honest with myself about past experiences, I see that desperation and attachment to outcomes were not a central feature of realizing the goals that have been deeply meaningful in my life. For example, during my second year of graduate school, I grew increasingly uncertain about pursuing a doctorate degree, largely because my department did not feel like a good fit for me and my renegade goals. I spoke with my advisor about whether or not to again apply for a fellowship I had unsuccessfully sought the previous year. It would pay for the rest of my schooling and allow me to focus more intently on my studies. She asked if I would choose to stay in the program if I received the fellowship, and I was quick to say "Yes." However, I already had a plan B in place and no longer felt I needed the fellowship to accomplish what I wanted to accomplish vocationally. Lo and behold, I approached the application process much more calmly than I had the year before and had the presence of mind to do a little research about the professors who selected the award recipients so that I better knew my audience. I felt like the essay I submitted authentically represented my academic vision and let go of the outcome. Needless to say, I got the fellowship and ultimately completed the program and my dissertation in ways that honored who I was as well as my commitments to social justice and arts-based research.

In contrast, when I decided to leave academia to pursue becoming a therapist, I did not initially have a job. Increasingly desperate to land work that would pay my bills, I accepted an offer for a position that had a good salary but that was in an organization with which I did not share several core values. Afraid of ongoing unemployment and its financial consequences, I pulled myself out of another job search in which I was a finalist to accept the offer. That second organization had felt like home during the interview process. Less than a year after I took the first job, I was fired. The job was a terrible fit for me, and I had taken several vocal stands against one of the projects the organization was pursuing on ethical grounds. Being fired was a humiliating experience, and, years later, I am still healing from the shame of it.

I do not mean to be polyannaish about hootlessness. Sometimes we've got to do what we've got to do to get by, even if several red flags are smacking us in the face while we do so. But we oftentimes give in to our deepest fears when our wanting mind takes over. We then go about our lives in ways that create a lot of unnecessary suffering. That suffering can be a great teacher, to be sure. Being fired from that job was what my supervisor would call "another fucking growth opportunity" that helped me realize a depth of clarity about my path that I might not have attained without the experience. Going forward, however, I can approach my wants with more awareness about the ties that bind me and, to the best of my ability, release them.

Aspiring to become hootless is akin to what Pema Chodron deems experiencing hopelessness: "giving up all hope of alternatives to the present moment, we can have a joyful relationship with our lives, an honest, direct relationship that no longer ignores the reality of impermanence and death." Embracing the uncertainty of life and inevitability of death while pursuing our goals is damn hard. But the benefits of doing so certainly outweigh the costs. The late John O'Donohue captures the fruits of becoming hootless with his beautiful poetry:

May I have the courage today

To live the life that I would love,

To postpone my dream no longer

But do at last what I came here for

And waste my heart on fear no more

May I live this day

Compassionate of heart,

Clear in work,

Gracious in awareness,

Courageous in thought,

Generous in love.

U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb's recent ruling of Wisconsin's constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage as unconstitutional has inspired me to write about the direction in which I would like to see my own field of "marriage and family therapy" go.

U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb's recent ruling of Wisconsin's constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage as unconstitutional has inspired me to write about the direction in which I would like to see my own field of "marriage and family therapy" go.

ed up

ed up